Women Who

Lead NIH’s

COVID Response

This Women’s History Month, EDI celebrates and acknowledges women in leadership positions at the NIH, leading in the NIH COVID response. We will not only highlight their work but the women behind it. These influencers of change shared their personal and professional stories illustrating their steps in their illustrious careers. We hope that their stories will allow other women and girls to see themselves and know what is possible for them.

NIH’s Women Who Lead

Julie Berko

Director, OHR

What is your role at the NIH?

As the Chief People Officer at NIH, I am responsible for all things people - my organization provides a wide variety of services to all members of the NIH workforce, and supports our federal employees at every step of their NIH journey.

What is your role related to the COVID response?

My role in the COVID response has been multifaceted as I lead my staff in navigating all of the NIH workforce issues related to COVID such as the return to physical workspaces plan, new pay and leave flexibilities, transitioning functions such as onboarding and our NIH Training Center to fully virtual, and more.

What has been your biggest challenge (personally or professionally) since the COVID outbreak?

Personally, my biggest challenge since the COVID outbreak has been navigating working full-time while supporting my two children who are remote learning.

What are you most proud of (professionally and/or personally)?

I am proud that I had a team and an organization that was adequately prepared to take on the challenges presented by the pandemic and transition seamlessly to the telework environment.

I have also realized the importance of surrounding myself with a good support system, both personally and professionally.

What are you hopeful for?

I have always been a big proponent of workplace flexibilities, having implemented many of the programs that we have here at the NIH, and I am hopeful that we can transfer many of the successful practices we’ve perfected while teleworking during the pandemic into the future of work and our new normal.

What do you know for sure?

More people will be teleworking and using various flexibilities that they never thought they would be willing to try or that could be used in their field.

What in your life prepared you for this responsibility?

Dealing with the adversity of a cancer diagnosis and pregnancy while also attending graduate school prepared me to handle just about anything. Over time I have also realized the importance of surrounding myself with a good support system, both personally and professionally, because there will always be challenges and it is crucial to lean on others around you.

What do you do for yourself when not focused on COVID or your other commitments?

In my free time I love to craft. I have recently been creating cards for friends and family, and photo books of past events and travels.

What advice would you give to those who look up to you?

At NIH, the currency that reigns is relationships and it’s really important to get outside of your bubble to expand your network. Finding out the people you need to know and building relationships with them – whether that is through a workgroup, informational interviews, or other engagements – is how things get accomplished here.

Dr. Emmie de Wit

Chief, Laboratory of Virology, NIAID

What is your role at the NIH?

I am the chief of the Molecular Pathogenesis Section in the Laboratory of Virology at Rocky Mountain Laboratories (part of NIAID) in Hamilton, Montana. I am a tenure track investigator and in my lab, we do research on emerging viruses that cause respiratory tract disease, more specifically, we are trying to understand how these viruses cause disease. We are mainly interested in viruses that can cause severe disease in humans, so our focus is on Nipah virus, the 1918 Spanish influenza virus and, since January 2020, SARS-CoV-2.

What is your role related to the COVID response?

Since my lab focuses on emerging viruses that cause respiratory disease, we immediately became interested in SARS-CoV-2 in January of 2020, when it still seemed like this was just an outbreak in Wuhan, China. We were one of the first labs to develop an animal model to study how the SARS-CoV-2 virus causes disease and we then used this model to show that, if you treat animals early after infection, remdesivir treatment can protect from developing a COVID-19 pneumonia. My lab also contributed to studies showing the efficacy of vaccine candidates in animals; studies that were necessary before the vaccines could be tested in clinical trials in humans.

What has been your biggest challenge (personally or professionally) since the COVID outbreak?

Just like for everyone else it has been hard at times to work efficiently within the restrictions of working safely during a pandemic. This was the first time we had to make backup lists of personnel that could step in if others would be quarantined or isolated, and then a backup list for the backup list, just so we could continue our work.

Stop questioning yourself all the time, sometimes you just have to take the leap.

On a personal level, it has been hard at times not to worry too much about loved ones becoming severely ill. As a virologist, I tend to think mostly about all the things that can go wrong if someone has COVID-19.

What are you most proud of (professionally and/or personally)?

I am very proud of the people in my lab; although my lab had only just started a few months before the pandemic I think they are a shining example of teamwork. Everyone has worked tirelessly to get the job done without complaints, whether they were doing the cool or boring parts of an experiment. On top of that, all the people here at RML really went out of their way to help us as soon as we started our work on COVID-19. Everyone ranging from scientists to support staff has been extremely dedicated to do their part to help us get the work done without delays so antivirals and vaccines could move forward into human clinical trials.

What are you hopeful for?

For everyone to get their COVID-19 vaccine! The worst may not be over yet, but the end of this pandemic is coming within sight now. If we can all stay strong for a few more months, follow the CDC guidelines to prevent transmission and then get vaccinated when it is our turn, life will return to normal before the end of this year. I can’t wait for the day this crisis is over and I can hug my family and friends again!

What do you know for sure?

New viruses like SARS-CoV-2 will keep emerging in the future. Luckily, we have learned so much during this pandemic, e.g. about new vaccine technologies, that we will be able to respond even faster when a new virus emerges.

What in your life prepared you for this responsibility?

Ever since there was an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (bird flu) while I was doing my PhD, I have been fascinated with disease outbreaks caused by viruses. Over the years, I had worked on several outbreaks (influenza and Ebola virus) and even a pandemic (2009 H1N1 influenza), so I had a lot of experience in defining what questions need to be answered when a new virus emerges, which of those questions fall within the expertise of my lab, and how to answer them as fast as possible.

What do you do for yourself when not focused on COVID or your other commitments?

My bicycles (a road bike and a mountain bike) are essential for maintaining my sanity. Even when the workload is extreme like it was over the last year, a few bike rides every week will keep me going - of course it helps that we are surrounded by beautiful scenery here in Montana.

What have you learned about yourself and or others in the past year?

I have been pleasantly surprised by scientists’ willingness to share data and reagents before publication. This has really helped to speed up the rate of discovering how this virus causes disease and the development of treatments and vaccines. I hope some of that attitude remains after the pandemic and we can tackle other big public health issues together in the most efficient way.

What advice would you give to those who look up to you?

Stop questioning yourself all the time, sometimes you just have to take the leap. And if you don’t like where you end up, you can always change your plans. In science, it is sometimes hard to know if you really fit in, especially if you don’t see a lot of role models who look like you – when I was doing my PhD there were no female PIs in my department, even though this was a big department; during both my postdocs there was only one. That doesn’t mean you don’t belong, and it doesn’t mean you can’t succeed. What worked really well for me was to find one or two peers who were also really into virology – we talked about our science and issues in the lab all the time, and as we are getting older, our problems may have changed a bit but we keep mentoring and encouraging each other.

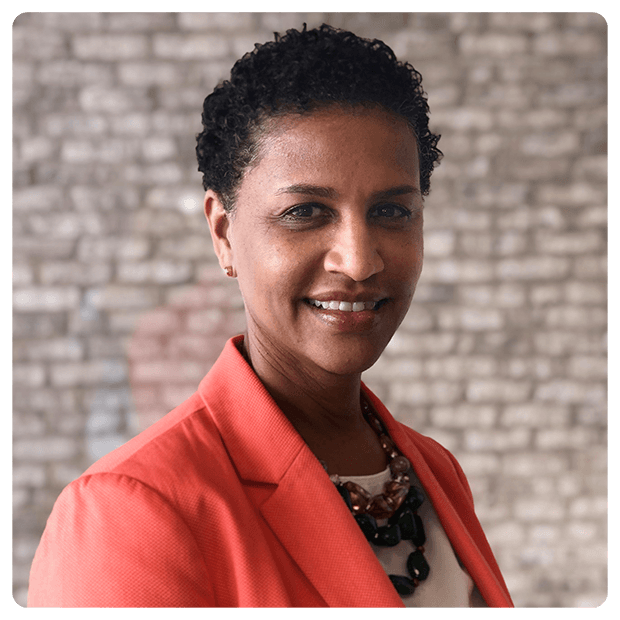

Dr. Monica Webb Hooper

Deputy Director, NIMHD

What is your role at the NIH?

I am Deputy Director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). My role commenced in March 2020, and I work closely with the Director, Dr. Pérez-Stable, and the leadership, to oversee all aspects of the institute and to support the implementation of the science visioning recommendations to improve minority health, reduce health disparities, and promote health equity. It’s an unparalleled honor and responsibility for me.

What is your role related to the COVID response?

As you know, COVID-19 is a global crisis. Its disproportionate toll on racial/ethnic minorities and other underserved populations has thrust health disparities into the national spotlight. I have been humbled to have a significant role in the scientific response to COVID-19, particularly focused on several large-scale initiatives to address the pandemic in underserved and vulnerable communities. I started my NIH career in tandem with the pandemic becoming a pandemic, and as early data revealed racial/ethnic disparities, the NIMHD Director, Dr. Eliseo Pérez-Stable, entrusted me immediately with leading Working Groups focused on (1) interventions to address the social, economic, and behavioral impacts of COVID-19, (2) increasing access and uptake of COVID-19 testing [Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics – Underserved Populations (RADx-UP)], and (3) addressing misinformation and distrust as well as facilitating diversity in COVID-19 clinical trials [Community Engagement Alliance Against COVID-19 Disparities (CEAL)]. Working closely with NIMHD program scientists, I am also leading an initiative on research to address vaccine hesitancy, uptake, and implementation among populations that experience health disparities. In each of these efforts, I have infused my scientific background, experience as a community engaged investigator, and my voice from the very beginning. Importantly, the data derived from these projects will evolve the science on understanding disparities in COVID-19 infections, disease progression and outcomes, and on intervention approaches to promote equity.

What has been your biggest challenge (personally or professionally) since the COVID outbreak?

I was sworn in as Deputy Director the day before we transitioned to 100% telework due to the pandemic. While it could seem, on the surface, that this was an inopportune time to begin such a position, I don’t view it that way. My learning curve has been steep and intense, but the work is deeply meaningful. The professional challenge has been building relationships and learning about NIMHD and NIH in general in a remote context – but we’ve all learned to adapt and it’s going well, notwithstanding the challenges. I have found staff within NIMHD and across NIH to be highly supportive and helpful. The biggest personal challenge has been adjusting to a physically distanced lifestyle. My family and I are active and social, and the need to avoid travel and gathering is not easy – but I view it as a short-term sacrifice for health.

What are you most proud of (professionally and/or personally)?

I have been very fortunate to have many professional and personal accomplishments. I’ll start with personal. I am most proud of the family my husband and I have built. We have three children (ages 9, 7, and 5) who are smart, kind, and all-around amazing humans that make me proud daily. Professionally, I am most proud of the research teams and participants I have had the honor of leading and working with as a professor and investigator. These individuals made the success of multiple studies possible and made significant contributions to the body of knowledge in the areas of chronic illness prevention, mental health, addictions, and health behavior change.

[The hope is that] we don't return to normal, but that we re-invent normal so that equity is a reality.

What are you hopeful for?

I’m an eternal optimist, so I have high hopes in many areas of life. As it relates to COVID-19, I am hopeful that as we approach the summer and fall of 2021, the pandemic will be in the rear-view mirror. Wouldn’t that be fantastic?! To reach this goal, we must maintain the focus on public health and behavioral prevention strategies to prevent infection and create smooth pathways to vaccination for all. I hope that we reach herd immunity as soon as possible and that we don’t return to “normal,” but that we re-invent normal so that equity is a reality. I am also hopeful that this unfortunate pandemic has opened a window of opportunity for achieving greater equity in health care of all populations with health disparities.

What do you know for sure?

Here is what I know. Health disparities are rooted in social disadvantage and are among the most wicked problems of our time. COVID-19 disparities are new, but the fundamental causes are longstanding. The goal is health equity, which refers to all people having a fair and just opportunity to attain the highest level of health. It sounds like a simple concept and is a term that we hear with increasing frequency, yet conducting true equity work is quite the challenge. Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally and implementing intentional efforts to address avoidable inequalities and eliminate health and health care disparities (without worsening health in any population). It also requires a shift in how we design interventions and think about populations with health disparities, which are often at the individual level and include erroneous labels such as “hard-to-reach” or “difficult to treat.” That is, we need to move away from interventions that seek to “fix” populations with health disparities (i.e., deficit models) toward approaches that emphasize individual and community assets, intervene on upstream determinants, and that distribute resources proportional to the need. Given the current national and global emphasis on addressing health disparities and understanding the structural factors at the root of them, we are at an important juncture. If we capitalize on this momentum, I know that we have a real opportunity to see a breakthrough.

What in your life prepared you for this responsibility?

By training, I am a translational behavioral scientist and clinical health psychologist. Before joining NIMHD, I dedicated my career to the scientific study of minority health and racial/ethnic disparities, focusing on chronic illness prevention and health behavior change. In my academic positions, my program of community engaged research focused on understanding multilevel factors and biopsychosocial mechanisms underlying modifiable risk factors, such as tobacco use and stress processes, and the development of community responsive and culturally specific interventions. Also work on distrust for healthcare and biomedical research among underserved populations. These topics are highly relevant to COVID-19 disparities and the work we are doing to respond. The significant involvement of stakeholders at all levels and across disciplines, at community-based organizations, as well as lay community members is a must in the context of research among underserved populations. As an investigator, I was very “hands-on.” I was on the ground with my research staff and spent time out in the community meeting participants and hearing their stories. My research partners and the communities I serve know that I am one of them. Full stop. I valued those opportunities, and in-turn, our partnerships were very strong (and still are).

Dr. Jessica M. McCormick-Ell

Director, Division of Occupational Health and Safety, OD

What is your role at the NIH?

I am the Director for the Division of Occupational Health and Safety, located within the Office of Research Services in the Office of Management.

What is your role related to the COVID response?

My Division has a hand in almost every aspect of the COVID response. I am a member of the Office of Research Services Incident Management Team, the NIH Tactical Team, and my Division is responsible for setting and outlining the safe practices and recommendations for the NIH during the COVID-19 pandemic. We wrote the safety guidance document, advise on cleaning after someone tests positive, perform fit testing for clinical staff needing respiratory protection, provide safety oversight at the symptomatic testing car line, and guidance in risk assessments for all types of operations. OMS is one of our branches, overseeing the contact investigations, resulting and return to aspect for persons testing positive. Currently, we are heavily involved in the planning, rollout and administration of vaccines to the NIH community. I am the NIH Point of Contact for the State of Maryland and I assist with coordination for other NIH satellite campuses across the country. Additionally, DOHS continues to perform routine functions supporting research and clinical operations, and are very involved in supporting the researchers performing COVID-19 related research.

What has been your biggest challenge (personally or professionally) since the COVID outbreak?

My biggest challenge is that I joined the NIH right in the early/ mid-portion of the pandemic, in late April. It’s hard to make connections remotely, but I think I’ve been able to do so, it’s just a different approach. I have not had time to tour campus or meet people in person the way I would have liked. My professional challenge is closely linked personally. My family is new to Maryland, so everything is new to us, but we really love it here. In addition to the pandemic, we’ve been settling in, working, balancing dependent care responsibilities, finding local places to enjoy as much as possible and I hope we can soon really explore all the area has to offer. I know my son would love the Smithsonian museums and National Zoo.

What are you most proud of (professionally and/or personally)?

I am proud of the resilience and adventurous nature of my family, who allowed me to uproot and move them to Maryland so I could be here. I am so proud to be able to work alongside the dedicated and excellent staff within the NIH, the Office of Research Services and especially within DOHS. They are mission oriented, generous, kind, intelligent and thoughtful people, and have really welcomed me into the NIH community. Even after all these months, when I drive onto campus, I am in awe that I get to be here and contribute.

Never compare, and never believe that the "traditional" path is the only or the right path. Take the chances that feel right, and believe in yourself above all.

What are you hopeful for?

I am hopeful for more vaccines, quickly, and for people to continue to be patient, resilient and kind. I am hopeful that people will remember how they felt in March 2020, putting others in front of themselves, and understanding what is really needed to get the pandemic under control. I hope people will learn to trust science, scientists, doctors, and truly start to listen to us. Finally, I am so hopeful to get to meet all of my staff members in person, to travel to all our locations across the country, and one day to shake their hand, bump into them in the office, or down the hall. Some of them, after all these months, I still have not seen in person. I cannot wait until my next-door neighbor and I can have real, inside playdates.

What do you know for sure?

I know we will continue to work tirelessly for the NIH, and for our communities. Moving to Maryland and taking this position was exactly the right thing to do, even during a pandemic. I know I am surrounded by people who care deeply and always give everything they have.

What in your life prepared you for this responsibility?

I have been studying microbiology and infectious diseases plus safety for twenty years. I have taught many courses, which included pandemic preparedness. In my previous roles, I was part of pandemic planning, plus real-life incident such as a meningitis outbreak amongst undergraduates. I have been fortunate to learn over these years about coordination and collaboration, which I think has served me well so far. I will say though, despite all I know and have studied, I am not sure anything prepares you for a pandemic, unless you lived through one before. The anxiety is real, and even if you have logical ways to handle it, sometimes the unknown can be a challenge. For me, I trusted my instincts and my training. I asked for help when I needed it and took many walks to clear my head on the tough days. I trusted my colleagues for their expertise and advise and I know how to do my own research to inform my recommendations and actions. As with anything, there will be times of doubt, and times of failure, but I think taking one day at a time, writing out a list to stay focused helped me.

What do you do for yourself when not focused on COVID or your other commitments?

I spend time with my family, time outside in our lovely yard. We have a garden for the first time, and we love to be outside. I love to read, and take long walks, enjoying the quiet of our area. We live in the country, which is a change of pace for us, and it is truly beautiful. We also love to explore museums, restaurants, zoos, and hope that soon we will be able to do so in a way that is comfortable for us.

What have you learned about yourself and or others in the past year?

I’ve learned that although new is scary, jumping in and taking the risk is so completely worth it. We can get stuck in our routines and comfort, but sometimes, life on the other side of the unknown is so much richer, and many times no where near as scary as we picture it in our heads. It’s still hard, but the growth and expansion make it all worth it. Be brave, take the leap, never stop growing or pushing yourself to learn something new. If you work hard, anything is possible.

What advice would you give to those who look up to you?

Dreams don’t come easy. They take a lot of work, and much of that work is not glamorous, well received or sometimes appreciated. Work for your dream only for yourself, no one else. Don’t listen to anyone who says you cannot be what you dream to be. If anything, use that as motivation to do whatever your heart desires. Also, there is no one right path. In my career, I always felt different from my lab mates and colleagues, since my path was not traditional, and definitely not a straight one. I worried since I had multiple areas of experience, perhaps it was too broad and not focused. I learned joining the NIH, that all those experiences fit together in the way my Division operates, and had I not had those experiences, it would not have lead me here. Never compare, and never believe that the “traditional” path is the only, or the right path. Take the chances that feel right, and believe in yourself above all.

Colleen McGowan

Director, Office of Research Services

What is your role at the NIH?

I am the Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Office of Research Services (ORS). As the ORS Director, I plan and direct service programs for public safety and security operations, scientific and regulatory support programs, and a wide variety of other program and employee services. In my role, I advise the NIH Deputy Director for Management and other NIH senior staff on the management and delivery of technical and administrative services in support of the NIH research mission.

The ORS is home to over 2,000 staff – 500 FTE and 1,500 Contractors. We keep the NIH running – you can think of me as a City Manager – overseeing everything form the Fire Department, Police Department, we run the cafeterias, oversee the parking, childcare centers, gyms, etc. The ORS also has a lot of responsibility in the scientific arena as well –we run the library and provide support to our intramural researchers. We have the Division of Occupational Health and Safety (DOHS) and Fire Marshall, and Radiation Safety which makes sure our facilities are safe and comply with national regulations. Also, a component of DOHS is the Occupational Medical Service (OMS) and Employee Assistance Program that so integral to staff health and safety during the pandemic. We care for animals used in research in our Division of Veterinary Resources as well. We buy equipment, we service equipment. You’ve been seeing Tony Fauci everywhere and our Events Management folks are the ones who make those connections with all the news outlets. Our Medical Arts has been putting posters up all across campus. We deliver the mail, we have a division of international services that helps our foreign trainees, making sure that they can get here and do great work.

The ORS responds to the priorities of the NIH and IC Leadership, NIH employees, patients and others served by the NIH, by supporting an exemplary physical and service infrastructure that will effectively support new scientific challenges to strengthen the NIH mission, the unique NIH research environment, and enhance the quality of life for all who come in contact with the NIH.

What is your role related to the COVID response?

Our organization has had a tremendous role in the overall COVID-19 response for the NIH. We provide trans-NIH leadership of COVID-19 response activities that support staff health and continuity of NIH mission-centric functions. Our most significant roles include:

- The Division of Emergency Management (DEM) and Division of Fire & Rescue Services (DFRS) developed the ORS Incident Management Team (IMT) structure. This structure is responsible for the continual oversight of operations relating to the COVID-19 response, including the drive-through sampling site, call center, Personal Protective Equipment point of distribution, and Occupational Medical Service COVID-19 operations.

- ORS Safety & Emergency Response (SER) assisted Occupational Medical Service (OMS) in developing and implementing the COVID-19 call center as well as operational flow charts for COVID-19 response within the call center and OMS to facilitate processing the COVID-19 positive cases of NIH employees and staff members.

- The Division of Occupational Health and Safety (DOHS) developed the NIH Return to Work Safety Guidance document and associated safety video. We have provided digital and printable materials, both in English and Spanish, to the NIH community.

- DOHS presented to approximately 400 employees across NIH ICOs on COVID-19 Return to the Physical Workplace policies. DOHS also conducted more than 100 Activity Hazard Analyses for food service, childcare, shuttle buses, surgeries, library, supply stores, CIT, and security offices.

- Division of Amenities and Transportation Services (DATS) developed webinar series to provide resources for employees dealing with distance learning; coping w/ caregiver stress (adult and children); COVID-19 stress in general.

- Division of International Services (DIS) partnered with several NIH training programs to develop a plan for addressing research interruptions due to COVID-19.

- Collaboration between ORS and ORF to interpret and respond to the challenges of servicing the NIH Bethesda campus during COVID. Standard Operating Procedures were quickly devised utilizing skill sets from multiple subject experts across NIH.

- Partnered with NIAID and the CC to develop a genomic epidemiological sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 virus to determine if there similar strains to suggest potential workplace transmissions of the virus.

- In April 2020, OneNIH was developed in partnership with DOHS, OALM, and Division of Logistics Services (DLS) which is a strategic buying initiative to provide and ensure safe, approved, quality personal protective equipment is available to NIH customers through the NIH Supply Center.

- Last but not least, ORS is currently playing a pivotal role in the planning, coordination, and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine to our first responders and the general NIH employee population when applicable.

What has been your biggest challenge (personally or professionally) since the COVID outbreak?

Like most working parents, trying to make it all work. I physically go to work twice a week, and I feel fortunate that my kids are physically going to school. I am trying to do a better job of saying no, and setting some more solid work/home boundaries. I was intentional about contacting friends and family at the start of the pandemic, but have slacked off on that. I need to connect more frequently virtually with my loved ones.

What are you most proud of (professionally and/or personally)?

The unifying spirit of the NIH family. Groups of people who normally don’t work together have an opportunity to come together and solve some really tough problems. We don’t have time for dissonance or worrying about personal status when you are battling a common enemy—SARS-CoV2. We developed a world-class carline sampling center in 1 week, we set up a vaccine administration center to accommodate 400 patients a day in 48 hours. We just get things done in ORS!

What are you hopeful for?

That we recognize what connects us instead of what divides us. I am hopeful that 2021 brings unity and an end to COVID-19!

What do you know for sure?

Life is unpredictable. Having a great team at home and at work, a sense of purpose, and an ability to maintain a sense of humor, you can get through anything. In these uncertain and often difficult times, never lose sight that we are all in this together.

It's OK to say I need help, and not be embarrassed to say I need a moment for self-care.

What in your life prepared you for this responsibility?

I had a pretty nomadic lifestyle as a kid. My dad was in the US Marine Corps, and then I followed in his footsteps when I joined the Air Force. I moved 20 times by the time I was 33 years old, so change was a way of life for me. I lived in different countries, had to learn to make new friends, and adjust to different cultures. While in the Air Force, I was stationed in South Korea and did emergency management. I then transitioned to hospital administration and worked in Air Force hospitals in California. That healthcare connection is what brought me to the NIH.

My military upbringing taught me resilience, which certainly is coming into play at this time. The importance of planning, and having back-up strategies and a cool head if things go sideways. My hospital experience also helped me that hiring a creative team of can-do staff allows you to pivot quickly to get the job done. If you hire and nurture smart and dedicated people, you can do great things, and I feel the same way about my experience at ORS so far.

What do you do for yourself when not focused on COVID or your other commitments?

This is a stressful time period, no matter what your personal situation looks like. It’s important, now more than ever, that we look out for one another. Everyone responds differently to stress – each of us has our own coping mechanism. For me, I find time to get outside and go for a walk with my family, or sometimes on my own. I recently took my daughters mountain hiking on a day off from school and I find spending time in nature calming and restorative. I find that exercise and having a spiritual life helps me find balance and think of something larger than just myself.

What have you learned about yourself and or others in the past year?

I’ve learned that you never really know how you’re going to react in a crisis until you’re in one. You need to rely on your team, whether it is in your workplace, or your home life to help you. It’s OK to say I need help, and not be embarrassed to say I need a moment for self-care.

I am so thankful that I work at the NIH with such service-minded staff. The number of volunteers who have raised their hands to assist in developing COVID-19 related activities such as providing diagnostic testing and contact tracing for positive cases has been tremendous. We are so fortunate at NIH, and I feel blessed to be part of this team.

What advice would you give to those who look up to you?

Pursue your passion and you will find purpose. Treat everyone with respect and show genuine appreciation for others. We are all human beings with our strengths and weaknesses. As you rise through the ranks, assemble a complementary team—people with different backgrounds, technical expertise and perspectives, and you will have richer discussions and more positive outcomes.

Dr. Sharon Milgram

Director, Office of Intramural Training and Education

What is your role at the NIH?

I direct the Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE; www.training.nih.gov) in the Office of the Director. As the OITE director I am responsible for developing programs and providing resources that help over 5000 NIH trainees develop the scientific, career, professional and personal skills they need to become leaders in research and healthcare communities. In addition to overseeing trans-NIH policy and coordinating many research training programs, the OITE offers a comprehensive set of workshops, courses and boot camps to prepare our trainees for career success. I also work with scientific societies and colleagues in the extramural community to ensure that the resources and programs we develop at NIH are accessible to students across the U.S. and internationally.

What is your role related to the COVID response?

One of my main roles during the pandemic is to help trainees and the biomedical research community deal with all of the stressors thrown at us in the last year. We have run many webinars to teach our community about healthy striving, stress management, resilience and mental health. We also host mindfulness meditations and small groups discussions focused on stress management and resilience. We modified our career advising and other training programs to work efficiently in a remote environment; some of these programs like postbac poster day, the career symposium and the graduate and professional school fair involve dozens of speakers and thousands of participants. Since the start, my mantra has been “change it don’t cancel it” and we have done our best to honor that intention.

At the outset of the pandemic, we set out to develop new workshop series that included small group discussions using Zoom. Two series that I am especially excited about are our “Becoming a Resilient Scientist” series and our series on social justice, diversity and inclusion. Both of these series include lectures and small group discussions and give our community a sense of togetherness even in this virtual world.

Finally, another important role has been to work with other NIH offices to develop policy related to trainee appointment and extensions during the pandemic. We developed policies on fellowship extensions, worked with the Division of International Services to support our international trainees and have dealt with the complexities of the 2020 and 2021 Summer Internship Programs. I prefer people over policy but appreciate how important the policy piece is during these unprecedented times.

When I lecture and meet with trainees individually and in small groups, I cannot help but feel hopeful for the future.

What has been your biggest challenge (personally or professionally) since the COVID outbreak?

Like for many of us, maintaining balance and finding time for myself has been a challenge since we started maximal telework. I try to be intentional about finding time to be with my wife, the friends we see outside and at a distance, and our extended family (all remotely). I also try hard to find time for myself – to cook, walk, bike, box and play tennis. When I find time for the things I love to do, I find that I can focus better when I am at work and also tend to be a bit more creative in solving problems. Being an extrovert in a virtual world has also been challenging at times. I am very aware of being a good role model for my staff and for the trainees I teach so I often think about finding balance and setting realistic expectations.

What are you most proud of (professionally and/or personally)?

I am proud of the OITE staff who are remarkably dedicated, committed and kind people who have gone above and beyond to provide services for trainees here at NIH and far beyond. They provided uninterrupted support to our NIH trainees, expanded our offerings with creative programming, and found ways to open most of our activities to trainees outside of NIH. They also support each other; we keep each other posted on our families using our Slack channel and I love when kids and pets make an appearance at our meetings. In my personal life, I am really proud of our son, Wonder. At the beginning of 2020, he drove across the country and relocated to California. The pandemic started shortly after he got settled there but he persisted and is finding ways to thrive. We miss him a lot and cannot wait for when it is safe to travel so we can see him!

What are you hopeful for?

I have been a scientist and science educator for a long time, and I believe that this generation of trainees will change science for the better. I tell them this all of the time, and I really believe it is true. They care about racial equity, health disparities, addressing bullying and harassment in research groups, healthy work-life boundaries, etc. When I lecture and meet with trainees individually and in small groups, I cannot help but feel hopeful for the future.

What do you know for sure?

It is hard to know anything for sure these days! That said, I believe that we have all grown through this challenge and that we will return to campus to be together at some point soon with a renewed sense of focus and purpose. I am also sure that we will all continue to use Zoom and will find opportunities to connect with NIH colleagues on other campuses using the lessons learned this last to keep trainees on remote campuses involved in the NIH community.

Renate Myles

Deputy Director, Public Affairs in the NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison

What is your role at the NIH?

Deputy Director for Public Affairs in the NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison

What is your role related to the COVID response?

I manage three branches that lead staff and public communication for NIH’s COVID-19 response. This includes launching the NIH Guidance for Staff on Coronavirus intranet page with more than 150 frequently asked questions and critical information on NIH’s Return to the Physical Workplace and Vaccination Plan efforts; hosting 7 Virtual Town Halls that generally garner 20,000 live views; producing 15 Francis Collins: Home Edition videos; and providing writing support for more than 70 all staff messages that come from the NIH Director; and much more. These teams manage all of Dr. Collins news and social media activities, speaking activities, and blog activities, as well as major events such as the NIH Vaccination Launch Event;the Vice President Vaccination Event; and visits by President Trump and President Biden to the NIH campus. The team also manages all major announcements from the Office of the Director, including press rollouts for new program launches and results of the numerous vaccine and treatment trials through the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccine (ACTIV) partnership, and new diagnostic tests through the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) program.. This is on top of the teams’ normal activities managing the NIH clearance of media interview and news releases across all 27 institutes and centers, and so much. They are amazing.

What has been your biggest challenge (personally or professionally) since the COVID outbreak?

Managing my wellbeing and the wellbeing of my staff when the demands of the job are so high.

Try to outperform yourself in everything you deliver.

What are you most proud of (professionally and/or personally)?

I’m proud of the personal commitment that everyone on my team has to NIH and to the quality of their work.

What are you hopeful for?

I’m hopeful that we can continue to trust in each other and support one another when things get difficult.

What do you know for sure?

I know we will get through this pandemic and NIH will come out stronger at the end of it.

What in your life prepared you for this responsibility?

I was raised to have a very strong work ethic; I’m grateful to my parents for instilling that in me.

What do you do for yourself when not focused on COVID or your other commitments?

Spend time with my family and friends, and read (a lot).

What have you learned about yourself and or others in the past year?

I’ve learned that people can rise to any challenge when you believe in them.

What advice would you give to those who look up to you?

Try to outperform yourself in everything you deliver.

Dr. Tara Schwetz

Associate Deputy Director of NIH

What is your role at the NIH?

I am the Associate Deputy Director of NIH, which means I am responsible for or involved in a variety of different trans-NIH activities, spanning a broad scope of topics. Additionally, I serve as the “OD Deputy Director”.

What is your role related to the COVID response?

I have been helping to lead several COVID-19 related efforts – from the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) and Radical (RADx-rad) programs to the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for COVID-19 Research to the COVID-19 Mental Health Response Working Group. I also serve as a member of the COVID-19 Response Team (fondly known as the “7:30 am Club”).

What has been your biggest challenge (personally or professionally) since the COVID outbreak?

Balancing work and life, and trying to be sure my team is able to do so as well. And sleep!

What are you most proud of (professionally and/or personally)?

Lately, I have been really proud of my team. Much like many others across NIH, they have really stepped up and done great work under trying circumstances.

More personally, I am proud of my contribution to the RADx-UP program, which is helping to provide access to testing, better understand testing uptake and accessibility, and behaviors and attitudes towards testing in underserved and vulnerable populations that are in desperate need of public health measures to reduce the burden of COVID-19. It has been so rewarding to think back on it as a high-level, general idea and now see it come to fruition.

Additionally, when I look back on the volume of work that many of us were pumping out early in the pandemic, I’m amazed at how we were able to do it all!

People are resilient, adaptable, and agile. No matter what comes our way, we rise to the challenge.

What are you hopeful for?

2021 and getting to see everyone in person sometime soon.

What do you know for sure?

People are resilient, adaptable, and agile. No matter what comes our way, we rise to the challenge. I have been so inspired by the people all across NIH, who have done amazing work to advance research, respond to the pandemic, and keep us all safe and healthy, while managing personal and professional challenges.

What advice would you give to those who look up to you?

For several years, I have said, “you can do anything for a year”. I feel like COVID-19 is really testing us all on this. But, I always follow it by saying that it can help you figure out what you enjoy, what you’re good at, and what you may not be as passionate about. When we eventually look back on it, the additional insight – and experience – gained will be a silver lining.