Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. reminded the world that, "Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable. Every step toward the goal of justice requires sacrifice, suffering, and struggle; the tireless exertions and passionate concern of dedicated individuals."

In observance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., here are the stories of eight peaceful protests that encouraged the civil rights movement.

Montgomery Bus Boycott, 1955-1956

Lasting over a year, the Montgomery Bus Boycott was a protest campaign against racial segregation on the public transit system in Montgomery, Alabama.

The boycott took place from December 5, 1955, to December 20, 1956, and is considered as the first large-scale U.S. demonstration against segregation. Four days prior to the start of the boycott, and the bravery of Rosa Louise McCauley Parks, an African-American, the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ordered Montgomery to integrate its bus system. Later, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., emerged as a prominent leader of the American Civil Rights Movement.

The Albany Movement, 1961

The Albany movement was an alliance formed in November 1961 in Albany, Georgia, to protest city segregation policies. Dr. King joined in the movement in December 1961, planning only to counsel the protesters for merely one day. He was jailed during a mass arrest of peaceful demonstrators, in a bold move, he declined bail until the city changed its segregation policies.

It was the first mass movement in the modern civil rights era to have as its goal the desegregation of an entire community, and it resulted in the jailing of more than 1,000 African Americans in Albany and surrounding rural counties. Dr. King was drawn into the movement in December 1961 when hundreds of black protesters, including himself, were arrested in one week, but eight months later King left Albany admitting that he had failed to accomplish the movement's goals. Albany was important because of King's involvement and because of the lessons he learned that he would soon apply in Birmingham, Alabama. Out of Albany's failure, then, came Birmingham's success.

The Birmingham Campaign, 1963

The Birmingham campaign was a strategic effort started by Dr. King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to end discriminatory economic policies in the Alabama city. The campaign lasted about two months.

In early 1965, the focus for Dr. King’s SCLC was registering black voters in the South. The founders were Dr. King, Ralph Abernathy, Baynard Rustin, Fred Shuttlesworth, and Joseph Lowery.

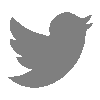

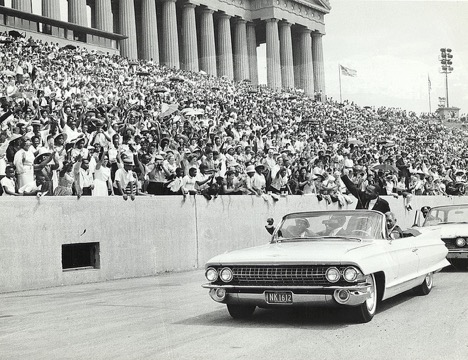

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 1963

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech advocating for racial harmony at Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Memorial.

The purpose of the march was to advocate for jobs and freedom. The March on Washington was a massive protest march that occurred on August 28, 1963, when 250,000 people gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was also known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the event aimed to draw attention to continuing challenges and inequalities faced by African Americans.

The 1963 March on Washington had several precedents. In the summer of 1941 A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, called for a march on Washington, D.C., to draw attention to the exclusion of African Americans from positions in the national defense industry. This job market had proven to be closed to blacks, despite the fact that it was growing to supply materials to the Allies in World War II. The threat of 100,000 marchers in Washington, D.C., pushed President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802, which mandated the formation of the Fair Employment Practices Commission to investigate racial discrimination charges against defense firms. In response, Randolph canceled plans for the march.

Civil rights demonstrators did assemble at the Lincoln Memorial in May 1957 for a Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom on the third anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, and in October 1958, for a Youth March for Integrated Schools to protest the lack of progress since that ruling. King addressed the 1957 demonstration, but due to ill health after being stabbed by Izola Curry, Coretta Scott King delivered his scheduled remarks at the 1958 event.

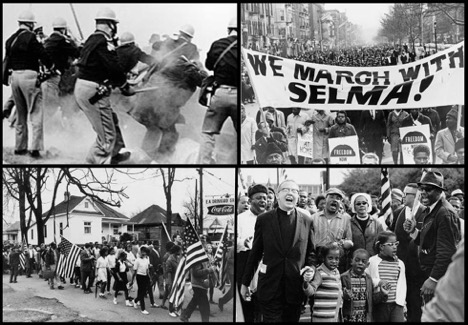

Selma’s Bloody Sunday, 1965

Top right: Marchers carrying banner "We march with Selma!" on street in Harlem, New York City, New York in 1965

Bottom left: Participants in the Selma to Montgomery march in Alabama during 1965

Bottom right: Dr. Martin Luther King, Dr. Ralph David Abernathy, their families, and others leading the Selma to Montgomery march in 1965. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The first, on Sunday, March 7, 1965, involved nearly 600 civil rights marchers who marched east from Selma on US Highway 80, led by Jon Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Rev. Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Dr. King was not present because he had church duties, but the day before the march he met with government officials in an effort to ensure that marchers would not be impeded. Despite his efforts, the peaceful marchers only made it as far as the Edmund Pettus Bridge, six blocks away from where there were confronted by a mob and state troopers violent attacks which caused the march to be aborted on that day.

King attempted to organize another march, but protesters did not succeed in getting to Montgomery until March 25. On this day, the speech he delivered, on the steps of the state capitol, has since become known as “How Long, Not Long.”

Bloody Sunday was a turning point for the Civil Rights Movement, it helped in building public support and demonstrating Dr. King’s strategy for non-violence.

Chicago Freedom Movement, 1966

With there being numerous successful demonstrations in the South, Dr. King, and other civil rights leaders sought to spread the movement north. They chose Chicago as their next destination to take on segregation and black urban problems.

Showing his commitment to the northern campaign, Dr. King rented an apartment in one of the worst areas of North Lawndale on the city's West Side. On a Friday afternoon in August, King guided approximately 700 people on a peaceful march in Marquette Park on Chicago’s Southwest Side, a white enclave, to protest housing segregation. King and his marchers were confronted by mobs of people who were not in agreement with the march. At one point, a brick hit Dr. King in the head, but he continued the march as onlookers hurled bottles, rocks, and firecrackers at the marchers. Thirty people were injured along with Dr. King.

King later said, "I have seen many demonstrations in the South, but I have never seen anything so hostile and hateful as I’ve seen here today." He continued, "I have to do this – to expose myself – to bring this hate into the open."

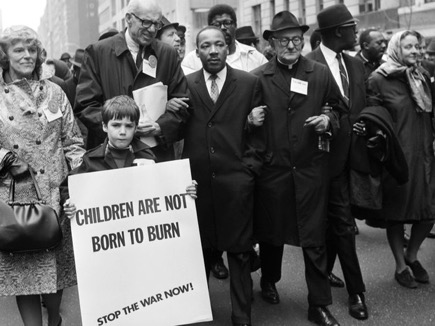

Vietnam War Opposition, 1967

At the United Nations headquarters in New York, Dr. King rallied an estimated 125,000 peaceful marchers on April 18, 1967, speaking of how the U.S. should end the bombing against North Vietnam. In addition, he appealed to students on organizing against the war.

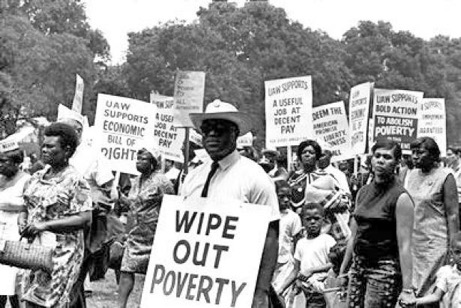

Poor People’s Campaign, 1968

Organized by Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1968, the so-called "poor people’s campaign" sought to address issues of economic justice and housing for the poor. King traveled the country to assemble a diverse group of protesters representing the poor who would march on Washington until Congress created a bill of rights for poor Americans.

After King's assassination in April 1968, SCLC members continued the campaign, organizing protests in Washington, D.C. Joined by D.C.'s poor and homeless, the protesters effectively shut down the city that summer. The bill of rights they envisioned never became law.

Do you have a story idea for us? Do you want to submit a guest blog? If it's about equity, diversity, or inclusion, please submit to edi.stories@nih.gov.

For news, updates, and videos, follow or subscribe to EDI on: Twitter, Instagram, Blog, YouTube.