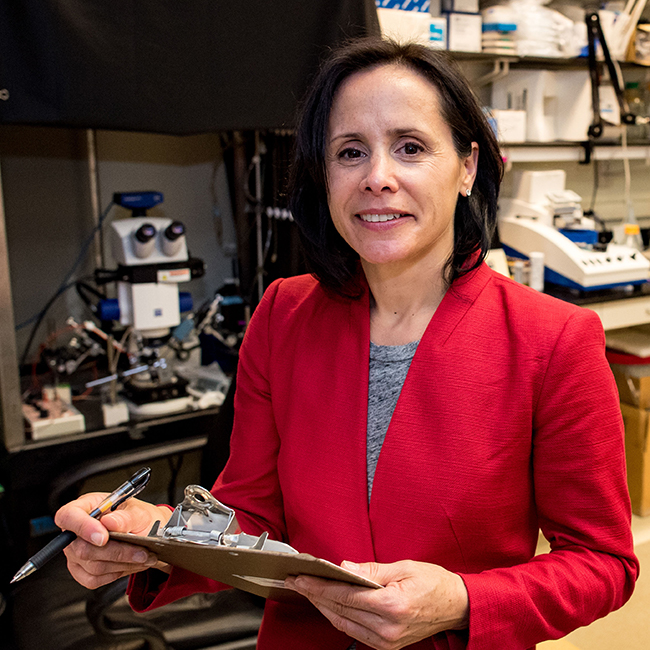

Veronica Alvarez, Ph.D.; Senior Investigator and Laboratory Chief, Laboratory on Neurobiology of Compulsive Behaviors (LNCB), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)

What inspired you to become a scientist?

Beginning when I was very little, my parents inspired me to become a scientist by valuing and nurturing my curiosity. My father shared his contagious amazement for nature and animals with me early on, and my mother always encouraged my individuality and independent thinking – traits that are essential in science. My mother also was and still is an incredible role model on how to juggle a career and family. Thirty years ago she raised five children while going through her medical residency and starting her own private practice, and to this day is a practicing OB/GYN doctor. She was a bit ahead of her time.

What gained your interest in the NIH?

I stumbled onto an opportunity to work at the NIH while I was finishing my postdoctoral training at Harvard Medical School. The opportunity became a reality thanks to the collaborative efforts of two Scientific Directors from different NIH Intramural Programs. Their work to bring me on board demonstrated that the NIH was a unique place to work where collaborative projects were not only possible but encouraged. That was a huge career attraction for me. I established my independent research program in 2008 and since then, our research has been growing and flourishing – thanks in part to the Intramural Program’s nurturing and collaborative environment. In 2017, I joined a group of neuroscientists to spearhead an initiative for collaborative studies, the Center on Compulsive Behaviors (CCB), which has been funded and supported by the Office of Scientific Directors of NIH (Dr. Gottesman) and leaders of seven other NIH Institutes. The Center focuses on understanding the brain mechanisms driving compulsive behaviors seen in addictions and neurological disorders such as Tourette Syndrome and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). With its growing collaborative effort between clinicians and basic scientists, the CCB is perfectly suited for the NIH research environment and I am very proud to be part of it.

What is your personal view on mentoring, and what have been some of your mentoring accomplishments as a scientific leader here at the NIH?

I am very aware of the long-lasting impact that mentors have. I wouldn't be in the position I am today without the influence and guidance of mentors who have helped me throughout my career with honest, thoughtful feedback and steady encouragement. Even as an independent investigator, I benefit enormously from the advice and support of mentors within the NIH – especially Dr. David Lovinger at NIAAA who has been my colleague and mentor for the past 10 years. He and other inspiring mentors throughout my career have fueled my desire to give back to my own mentees and contribute to their careers. Mentoring is like an investment that always pays high returns, and I see it as one of the primary responsibilities we have as scientists. Furthermore, mentoring offers a unique opportunity to share experiences and knowledge, build relationships with others, and shape someone else's mind and future. It's also an excellent way to keep learning; I always think of mentoring as a two-way interaction. Like parenting, the responsibilities of each member are not equal, but both sides have much to gain.

Why is diversity important for science?

We all have something unique to contribute, and I think this is especially true if you are different in some way. I used to feel intimidated every time I realized I was different from others or had an uncommon perspective. With time, the uncomfortable feelings have been replaced by an urge and a sense of empowerment. Knowing that I may carry a different perspective inspires me to open up and share. I tell myself: The people I interact with need to hear my side and it is up to me to be engaged so others can listen and learn as well.

Do you have a story idea for us? Do you want to submit a guest blog? If it's about equity, diversity, or inclusion, please submit to edi.stories@nih.gov.

For news, updates, and videos, follow or subscribe to EDI on: Twitter, Instagram, Blog, YouTube.